he book is modernity’s quintessential technology—“a means of transportation through the space of experience, at the speed of a turning page,” as the poet Joseph Brodsky put it. But now that the rustle of the book’s turning page competes with the flicker of the screen’s twitching pixel, we must consider the possibility that the book may not be around much longer. If it isn’t—if we choose to replace the book—what will become of reading and the print culture it fostered? And what does it tell us about ourselves that we may soon retire this most remarkable, five-hundred-year-old technology?

We have already taken the first steps on our journey to a new form of literacy—“digital literacy.” The fact that we must now distinguish among different types of literacy hints at how far we have moved away from traditional notions of reading. The screen mediates everything from our most private communications to our enjoyment of writing, drama, and games. It is the busiest port of entry for popular culture and requires navigation skills different from those that helped us master print literacy.

Enthusiasts and self-appointed experts assure us that this new digital literacy represents an advance for mankind; the book is evolving, progressing, improving, they argue, and every improvement demands an uneasy period of adjustment. Sophisticated forms of collaborative “information foraging” will replace solitary deep reading; the connected screen will replace the disconnected book. Perhaps, eons from now, our love affair with the printed word will be remembered as but a brief episode in our cultural maturation, and the book as a once-beloved technology we’ve outgrown.

But if enthusiasm for the new digital literacy runs high, it also runs to feverish extremes. Digital literacy’s boosters are not unlike the people who were swept up in the multiculturalism fad of the 1980s and 1990s. Intent on encouraging a diversity of viewpoints, they initially argued for supplementing the canon so that it acknowledged the intellectual contributions of women and minorities. But like multiculturalism, which soon changed its focus from broadening the canon to eviscerating it by purging the contributions of “dead white males,” digital literacy’s advocates increasingly speak of replacing, rather than supplementing, print literacy. What is “reading” anyway, they ask, in a multimedia world like ours? We are increasingly distractible, impatient, and convenience-obsessed—and the paper book just can’t keep up. Shouldn’t we simply acknowledge that we are becoming people of the screen, not people of the book?

To Read or Not to Read Every technology is both an expression of a culture and a potential transformer of it. In bestowing the power of uniformity, preservation, and replication, the printing press inaugurated an era of scholarly revision of existing knowledge. From scroll, to codex, to movable type, to digitization, reading has evolved and the culture has changed with it. In A History of Reading, Alberto Manguel reminds us that the silent reading we take for granted didn’t become the norm in the West until the tenth century. Far from the quiet contemplation we imagine, monasteries were actually “communities of mumblers,” as critic Ivan Illich once described, where devotional reading was constant and aloud.

Just as our styles of reading have changed, so too have our reasons for reading and the amount of time we devote to it. “Read in order to live,” Flaubert wrote. Critic Harold Bloom views reading from the other end of the human lifespan. “One of the uses of reading is to prepare ourselves for change,” he argues in How to Read and Why, “and the final change alas is universal.” But however much we read and for whatever reasons, literacy has long been prized as a marker of civilization and a measure of a society’s success. Literacy is now nearly universal in the United States and the rest of the developed world—a remarkable historical achievement, and yet one that has sparked more complacency than comment.

That may be changing. In 2007, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) published a report, To Read or Not To Read: A Question of National Consequence, which provided ample evidence of the decline of reading for pleasure, particularly among the young. To wit: Nearly half of Americans ages 18 to 24 read no books for pleasure; Americans ages 15 to 24 spend only between 7 and 10 minutes per day reading voluntarily; and two thirds of college freshmen read for pleasure for less than an hour per week or not at all. As Sunil Iyengar, director of the NEA’s Office of Research and Analysis and the lead author of the report, told me, “We can no longer take the presence of books in the home for granted. Reading on one’s own—not in a required sense, but doing it because you want to read—that skill has to be cultivated at an early age.” The NEA report also found that regular reading is strongly correlated with civic engagement, patronage of the arts, and charity work. People who read regularly for pleasure are more likely to be employed, and more likely to vote, exercise, visit museums, and volunteer in their communities; in short, they are more engaged citizens.

Not everyone endorses this claim for reading’s value. Bloom, for instance, is not persuaded by claims that reading encourages civic engagement. “You cannot directly improve anyone else’s life by reading better or more deeply,” he argues. “I remain skeptical of the traditional social hope that care for others may be stimulated by the growth of individual imagination, and I am wary of any arguments whatsoever that connect the pleasures of solitary reading to the public good.”

Whether one agrees with the NEA or with Bloom, no one can deny that our new communications technologies have irrevocably altered the reading culture. In 2005, Northwestern University sociologists Wendy Griswold, Terry McDonnell, and Nathan Wright identified the emergence of a new “reading class,” one “restricted in size but disproportionate in influence.” Their research , conducted largely in the 1990s, found that the heaviest readers were also the heaviest users of the Internet, a result that many enthusiasts of digital literacy took as evidence that print literacy and screen literacy might be complementary capacities instead of just competitors for precious time.

But the Northwestern sociologists also predicted, “as Internet use moves into less-advantaged segments of the population, the picture may change. For these groups, it may be that leisure time is more limited, the reading habit is less firmly established, and the competition between going online and reading is more intense.” This prediction is now coming to pass: A University of Michigan study published in the Harvard Educational Review in 2008 reported that the Web is now the primary source of reading material for low-income high school students in Detroit. And yet, the study notes, “only reading novels on a regular basis outside of school is shown to have a positive relationship to academic achievement.”

Despite the attention once paid to the so-called digital divide, the real gap isn’t between households with computers and households without them; it is the one developing between, on the one hand, households where parents teach their children the old-fashioned skill of reading and instill in them a love of books, and, on the other hand, households where parents don’t. As Griswold and her colleagues suggested, it remains an open question whether the new “reading class” will “have both power and prestige associated with an increasingly rare form of cultural capital,” or whether the pursuit of reading will become merely “an increasingly arcane hobby.”

There is another aspect of reading not captured in these studies, but just as crucial to our long-term cultural health. For centuries, print literacy has been one of the building blocks in the formation of the modern sense of self. By contrast, screen reading, a historically recent arrival, encourages a different kind of self-conception, one based on interaction and dependent on the feedback of others. It rewards participation and performance, not contemplation. It is, to borrow a characterization from sociologist David Riesman, a kind of literacy more comfortable for the “outer-directed” personality who takes his cues from others and constantly reinvents himself than for the “inner-directed” personality whose values are less flexible but also less susceptible to outside pressures. How does a culture of digitally literate, outer-directed personalities “read”?

Promiscuous, Diverse, and Volatile The NEA’s study was not without its critics, many of whom focused on the report’s definition of reading as limited to print content. Steven Johnson, author of Everything Bad Is Good For You: How Today’s Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter (2005), was miffed that the report didn’t include screen reading in its analysis. “I challenge the NEA to track the economic status of obsessive novel readers and obsessive computer programmers over the next ten years,” he wrote in the London Guardian. “Which group will have more professional success in this climate?” he asked. This question is obtuse and misguided, although not surprising coming from a reflexive techno-utopian like Johnson. Most of the people immersed in screen worlds are not programmers. They are consumers who are reading on the screen, but also buying, blogging, surfing, and playing games. How can we differentiate among these many activities, not all of which might contribute to the success Johnson prizes?

Johnson would have done better to compare obsessive novel writers and obsessive computer programmers (I would guess that Danielle Steele’s paychecks measure up to those earned by the programmers of Grand Theft Auto). More importantly, although computer programmers undoubtedly enjoy great success “in this climate,” as Johnson notes, he entirely misses the point: that “this climate” itself is what the NEA report is challenging. Johnson’s dismissive response is akin to praising people who react to global warming by becoming nudists.

Besides, the NEA was well aware of the difficulties involved in measuring screen and print reading. As Iyengar told me, “In terms of working definitions of reading—reading on computers or online—these pose challenges to survey methodologists.” But he recognizes the need for such data. “For the future, we need better ways to get at the question of reading on the screen versus not. We have a massive amount of data on reading in the traditional sense. I think the jury is out on whether or not those same benefits transfer to screen reading.”

But the jury is nearing a verdict. While the testimonials of digital literacy enthusiasts are replete with abstract paeans to the possibilities presented by screen reading, the experience of those who do it for a living paints a very different picture. Just as Griswold and her colleagues suggested the impending rise of a “reading class,” British neuroscientist Susan Greenfield argues that the time we spend in front of the computer and television is creating a two-class society: people of the screen and people of the book. The former, according to new neurological research, are exposing themselves to excessive amounts of dopamine, the natural chemical neurotransmitter produced by the brain. This in turn can lead to the suppression of activity in the prefrontal cortex, which controls functions such as measuring risk and considering the consequences of one’s actions.

Writing in The New Republic in 2005, Johns Hopkins University historian David A. Bell described the often arduous process of reading a scholarly book in digital rather than print format: “I scroll back and forth, search for keywords, and interrupt myself even more often than usual to refill my coffee cup, check my e-mail, check the news, rearrange files in my desk drawer. Eventually I get through the book, and am glad to have done so. But a week later I find it remarkably hard to remember what I have read.”

As he tried to train himself to screen-read—and mastering such reading does require new skills—Bell made an important observation, one often overlooked in the debate over digital texts: the computer screen was not intended to replace the book. Screen reading allows you to read in a “strategic, targeted manner,” searching for particular pieces of information, he notes. And although this style of reading is admittedly empowering, Bell cautions, “You are the master, not some dead author. And that is precisely where the greatest dangers lie, because when reading, you should not be the master”; you should be the student. “Surrendering to the organizing logic of a book is, after all, the way one learns,” he observes.

How strategic and targeted are we when we read on the screen? In a commissioned report published by the British Library in January 2008 (the cover of which features a rather alarming picture of a young boy with a maniacal expression staring at a screen image of Darth Vader), researchers found that everyone, teachers and students alike, “exhibits a bouncing/flicking behavior, which sees them searching horizontally rather than vertically....Users are promiscuous, diverse, and volatile.” As for the kind of reading the study participants were doing online, it was qualitatively different from traditional literacy. “It is clear that users are not reading online in the traditional sense, indeed there are signs that new forms of ‛reading’ are emerging as users ‛power browse’ horizontally through titles, contents pages, and abstracts going for quick wins.” As the report’s authors concluded, with a baffling ingenuousness, “It almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.”

That is precisely what Jakob Nielsen, a former software engineer and a widely respected expert on Web page usability, found in his research on screen reading. Rather than reading deliberately, when we scan the screen in search of content our eyes follow an F-shaped pattern, quickly darting across text in search of the central nugget of information we seek. “‛Reading’ is not even the right word” to describe this activity, Nielsen pointedly says.

Evidently not. In a spate of recent stories about changes in literacy, writers have taken to using scare quotes to signal the now-liminal status of the printed word. Last year, when the New York Times interviewed the chief executive of Scholastic Publishing, he was remarkably unworried about the effects of screen time on traditional reading skills. “We’ll see more about the impact of technology and the interaction between graphics and words,” he said, but since reading is “visualizing in your mind, there could easily be a rebirth of intellectual activity, whether you call it ‛reading’ or not.”

“I think we have to ask ourselves, ‛What exactly is reading?’” said Jack Martin, assistant director for young adult programs at the New York Public Library, in another Times story. “Reading is no longer just in the traditional sense of reading words in English or another language on paper.” As the Times went on to report, rather uncritically, “Spurred by arguments that video games also may teach a kind of digital literacy that is becoming as important as proficiency in print, libraries are hosting gaming tournaments, while schools are exploring how to incorporate video games into the classroom.” The MacArthur Foundation is pouring money into an effort to use video games to promote learning in public schools in New York. “I wouldn’t be surprised if, in ten or twenty years, video games are creating fictional universes which are every bit as complex as the world of fiction of Dickens or Dostoevsky,” said Jay Parini, a writer who teaches English at Middlebury College. Little Dorrit, meet Dora the Explorer!

The new caveats about “reading” are part of a broader argument that advocates of digital literacy promote: digital literacy, unlike traditional print literacy, they argue, is not “passive.” The screen invites the player of a video game to put himself at the center of the action, and so it must follow that “games are teaching critical thinking skills and a sense of yourself as an agent having to make choices and live with those choices,” says James Paul Gee, one of the chief cheerleaders of video games as learning tools. As Gee told the Times, “You can’t screw up a Dostoevsky book, but you can screw up a game.”

Parini’s and Gee’s statements suffer from a profound misunderstanding of the reading experience and evince an astonishing level of hubris. The reason you can’t “screw up” a Dostoevsky novel is that you must first submit yourself to the process of reading it—which means accepting, at some level, the author’s authority to tell you the story. You enter the author’s world on his terms, and in so doing get away from yourself. Yes, you are powerless to change the narrative or the characters, but you become more open to the experiences of others and, importantly, open to the notion that you are not always in control. In the process, you might even become more attuned to the complexities of family life, the vicissitudes of social institutions, and the lasting truths of human nature. The screen, by contrast, tends in the opposite direction. Instead of a reader, you become a user; instead of submitting to an author, you become the master. The screen promotes invulnerability. Whatever setbacks occur (as in a video game) are temporary, fixable, and ultimately overcome. We expect to master the game and move on to the next challenge. This is a lesson in trial and error, and often an entertaining one at that, but it is not a lesson in richer human understanding.

My Own Digital Dickens In a.d. 1000, the Grand Vizier of Persia, an avid reader, faced a peculiar logistical challenge when he traveled. Unwilling to leave behind his precious collection of 117,000 books, as historian Alberto Manguel tells us, he hit upon a unique strategy for transporting them: four hundred camels trained to walk in an alphabetically-ordered caravan behind him on his journey.

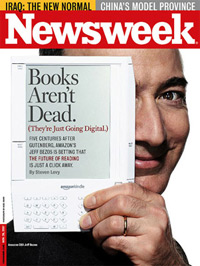

What the Grand Vizier needed was a Kindle. Since its much-hyped launch in 2007, Amazon’s portable electronic reader (if it is the “reader,” what does that make you?) has received outsized media attention. In a characteristically enthusiastic article about the device in Newsweek, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos was quoted as saying, “This is the most important thing we’ve ever done....It’s so ambitious to take something as highly evolved as the book and improve on it. And maybe even change the way people read.” The market for e-books, although growing rapidly, is still less than 1 percent of the total publishing business: perhaps 400 million paper books will be sold in the United States in 2008, and Amazon expects to sell 380,000 Kindles in 2008, resulting in an unknown number of book downloads.

What the Grand Vizier needed was a Kindle. Since its much-hyped launch in 2007, Amazon’s portable electronic reader (if it is the “reader,” what does that make you?) has received outsized media attention. In a characteristically enthusiastic article about the device in Newsweek, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos was quoted as saying, “This is the most important thing we’ve ever done....It’s so ambitious to take something as highly evolved as the book and improve on it. And maybe even change the way people read.” The market for e-books, although growing rapidly, is still less than 1 percent of the total publishing business: perhaps 400 million paper books will be sold in the United States in 2008, and Amazon expects to sell 380,000 Kindles in 2008, resulting in an unknown number of book downloads.

Much has been written about the Kindle’s various features: wireless service that allows for rapid delivery of e-texts; the ability to search the Web; a service called “NowNow” that performs real-time searches (using human beings!) to answer questions; a dedicated “Search Wikipedia” function. These features are remarkable—and remarkably distracting.

The screensaver on the Kindle I used featured literary personages of British descent: Oscar Wilde tricked out in fur-trimmed velvet, for example, and the ghostly visage of Virginia Woolf. Another more self-serving screensaver popped up later with a definition of “kindle” and the cloying explanatory sentence—By reading to me at bedtime when I was a child, my parents kindled my lifelong love for reading—in a weird evocation of childhood nostalgia for the very printed page the e-book’s pushers mean to supplant. (Kindle users have already figured out how to hack the Kindle screensaver function to use images other than the default ones, of course.)

A friend of mine who was an early Kindle user noted how much he enjoys the fact that the Kindle delivers the day’s newspapers to his device overnight, so he can read them first thing in the morning. He uses his Kindle for work travel a lot as well, and as one of those people who always ambitiously packed too many books for long plane flights, now enjoys the convenience of being able to bring dozens of books stored on one device. The Kindle also appeals to people who deal with a lot of paper in their jobs; publishers such as Random House are now distributing e-readers to editors to read manuscripts.

When Amazon sent me a Kindle to try, I had been reading a worn copy of Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby—a Penguin classic edition from the 1970s, with its distinctive orange paperback spine (and a list price of $3.95). Dickens seemed a good choice to read on the Kindle—after all, he was one of the great serial novelists, and the Kindle seems to lend itself to serial reading. Dickens’s adoption of monthly serialization—approximately thirty-two pages per month, sold in cheap editions for a shilling apiece (at a time when most Victorian novels were several volumes long and a great deal more expensive) represented a gutsy experiment in marketing and mass publishing—not unlike the Kindle. And his novels are all still in print.

The Kindle and other similar devices, such as Sony’s e-Reader, train users to read on screens intended to replicate the readability of paper and minimize eye strain; unlike bright computer monitors, the screens on these e-books are dull gray with black lettering, using a sophisticated “E Ink” display developed by M.I.T.’s Media Lab. Although mildly disorienting at first, I quickly adjusted to the Kindle’s screen and mastered the scroll and page-turn buttons. Nevertheless, my eyes were restless and jumped around as they do when I try to read for a sustained time on the computer. Distractions abounded. I looked up Dickens on Wikipedia, then jumped straight down the Internet rabbit hole following a link about a Dickens short story, “Mugby Junction.” Twenty minutes later I still hadn’t returned to my reading of Nickleby on the Kindle. I found that despite the ability to change the font size and scroll up and down the screen, reading was much slower on the Kindle than in book form. I’d want it on a long trip, but not for everyday use.

There are practical concerns as well: Despite Kindle’s emphasis on accessibility—get any book, anywhere, instantly—this is true only if you can afford to own the device that allows you to read it. You can’t share the books you’ve read on your Kindle unless you hand the device over to a friend to borrow. There are other drawbacks to the Kindle, more emotional than practical. Unlike a regular book, where the weight of the book transfers from your right hand to your left as you progress, with the Kindle you have no sense of where you are in the book by its feel. It doesn’t smell like a book. Nor does the clean, digital Kindle bear the impressions of previous readers, the smudges and folds and scribbles and forgotten treasures tucked amid the pages—markings of the man-made artifact. The printed book is the “transformation of the intangible into the tangibility of things,” as Hannah Arendt put it; it is imagined and lived action and speech turned into palpable remembrance. Such feelings of partiality to the printed book are impossible to quantify, and might well strike the critic as foolish attachment to an outmoded medium, as rank sentimental preference for the durable over the delible and digital. To be sure, “I just like the feel of it” is hardly firm intellectual footing from which to launch a defense of the paper book. But it is at least worth noting that these tactile experiences have no counterpart when reading on the screen, and worth recalling that for all our enthusiasm about the aesthetics of our technologies—our sleek iPhones and iPods—we are quick to discount the same kind of appreciation for printed words on paper.

Kids and Kindles It is also worth questioning what role the Kindle will play in the lives of younger readers. If there is such a thing as a culture of reading, it begins in the home. Regardless of their parents’ educational background or income level, children raised in homes with books become more proficient readers. Does this apply to the Kindle? Sven Birkerts, author of The Gutenberg Elegies (1994), describes how our screen technologies exert a “conditioning impact” on all of us who use them; that is, “they make it harder, once we do turn from the screen, to engage the single-focus requirement of reading.” This seems a particular danger for children. We already know that electronic books marketed for children, far from being helpful in teaching literacy, can hamper it. Researchers at Temple University’s Infant Laboratory and the Erikson Institute in Chicago who studied electronic books aimed at children described a “slightly coercive parent-child interaction as opposed to talking about the story,” and concluded, “We shouldn’t use e-books to replace traditional books.” Anyone who has read a book to a toddler knows that one experience with an e-reader would yield more interest in the buttons and the scroll wheel than the story itself.

Meanwhile, older children and teens who are coming of age surrounded by cell phones, video games, iPods, instant messaging, text messaging, and Facebook have finely honed digital literacy skills, but often lack the ability to concentrate that is the first requirement of traditional literacy. This poses challenges not just to the act of reading but also to the cultural institutions that support it, particularly libraries. The New York Times recently carried a story about the disruptive behavior of younger patrons in the British Library Reading Room. Older researchers—and by old they meant over thirty—lamented the boisterous atmosphere in the library and found the constant giggling, texting, and iPod use distracting. A library spokesman was not sympathetic to the neo-geezers’ concerns, saying, “The library has changed and evolved, and people use it in different ways. They have a different way of doing their research. They are using their computers and checking things on the Web, not just taking notes on notepads.” In today’s landscape of digital literacy, the old print battles—like the American Library Association’s “Banned Books Week,” held each year since 1982—seem downright quaint, like the righteous crusade of a few fusty tenders of the Dewey Decimal system. Students today are far more likely to protest a ban on wireless Internet access than book censorship.

Not every librarian is pleased with these changes. Some chafe at their new titles of “media and information specialist” and “librarian-technologist.” One librarian at a private school in McLean, Virginia, described in the Washington Post a general impatience among kids toward books, and an unwillingness to grapple with difficult texts. “How long is it?” has replaced “Will I like it?” he says, when he tries to entice a student to read a book. For an increasing number of librarians, their primary responsibility is teaching computer research skills to young people who need to extract information, like little miners. But these kids are not like real miners, who dig deeply; they are more like ’49ers panning for gold. To be sure, a few will strike a vein, stumbling across a novel or a poem so engrossing that they seek more. But most merely sift through the silty top layers, grab what is shiny and close at hand, and declare themselves rich.

The Kindle will only serve to worsen that concentration deficit, for when you use a Kindle, you are not merely a reader—you are also a consumer. Indeed, everything about the device is intended to keep you in a posture of consumption. As Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has admitted, the Kindle “isn’t a device, it’s a service.”

In this sense it is a metaphor for the experience of reading in the twenty-first century. Like so many things we idolize today, it is extraordinarily convenient, technologically sophisticated, consumption-oriented, sterile, and distracting. The Kindle also encourages a kind of utopianism about instant gratification, and a confusion of needs and wants. Do we really need Dickens on demand? Part of the gratification for first readers of Dickens was rooted in the very anticipation they felt waiting for the next installment of his serialized novels—as illustrated by the story of Americans lining up at the docks in New York to learn the fate of Little Nell. The wait served a purpose: in the interval between finishing one installment and getting the next, readers had time to think about the characters and ponder their motives and actions. They had time to connect to the story.

We are so eager to explore what these new devices do—particularly what they do better than the printed book—that we ignore the more rudimentary but important human questions: the tactile pleasures of the printed page versus the screen; the new risks of distraction posed by a device with a wireless Internet connection; the difference between reading a book in two-page spreads and reading a story on one flashing screen-display after another. Kindle and other e-readers are marvelous technologies of convenience, but they are no replacement for the book.

The Book Is Dead. Long Live the Book! A parallel debate about the meaning of texts and the future of reading is going on with regard to the efforts of Google (and others) to digitize the world’s libraries (a debate wherein, oddly, the word “bibliophile” is often hurled as an epithet but the word “technophile” is rarely uttered). John Updike’s cri de coeur at the 2006 BookExpo called on booksellers to “defend your lonely forts” against these and other challenges to the book, reminding his listeners, “For some of us, books are intrinsic to our human identity.”

Perhaps the most excitable dispatch from this front came from former Wired magazine editor Kevin Kelly in a 2006 article in the New York Times Magazine. This ode to gigajoy included the obligatory prediction that paper books would be replaced with handheld devices. “Just as the music audience now juggles and reorders songs into new albums,” Kelly writes, the universal digital library that Google is bringing into the world “will encourage the creation of virtual ‛bookshelves’—a collection of texts, some as short as a paragraph, others as long as entire books, that form a library shelf’s worth of specialized information.” Kelly anticipates the day when authors will “write books to be read as snippets or to be remixed as pages.” But what would a mash-up of George Eliot’s Middlemarch and the latest best-selling mystery look like? There are some extraordinary lines in Eliot’s novel. Writing of Lydgate and Rosamond, for example, Eliot says, “He once called her his basil plant; and when she asked for an explanation, said that basil was a plant which had flourished wonderfully on a murdered man’s brains.” But devoid of the complicated context of the rest of the novel, how can we understand why this observation is poignant, apt, and true?

Kelly’s hope for the book is to turn it into a kind of digital Frankenstein monster, a contextless “text” that is no more than the sum of its scattered and remixed parts: “What counts are the ways in which these common copies of a creative work can be linked, manipulated, annotated, tagged, highlighted, bookmarked, translated, enlivened by other media and sewn together into the universal library,” he writes. And he is confident that “in the clash between the conventions of the book and the protocols of the screen, the screen will prevail.” Perhaps it will, but Kelly might want to include in his own future e-book another snippet from Eliot’s masterpiece, one which might serve as a warning for us all: “We are on a perilous margin when we begin to look passively at our future selves, and see our own figures led with dull consent into insipid misdoing and shabby achievement.”

If reading has a history, it might also have an end. It is far too soon to tell when that end might come, and how the shift from print literacy to digital literacy will transform the “reading brain” and the culture that has so long supported it. Echoes will linger, as they do today from the distant past: audio books are merely a more individualistic and technologically sophisticated version of the old practice of reading aloud. But we are coming to see the book as a hindrance, a retrograde technology that doesn’t suit the times. Its inanimacy now renders it less compelling than the eye-catching screen. It doesn’t actively do anything for us. In our eagerness to upgrade or replace the book, we try to make reading easier, more convenient, more entertaining—forgetting that reading is also supposed to encourage us to challenge ourselves and to search for deeper meaning.

In a 1988 essay in the Times Literary Supplement, the critic George Steiner wrote,

I would not be surprised if that which lies ahead for classical modes of reading resembles the monasticism from which those modes sprung. I sometimes dream of houses of reading—a Hebrew phrase—in which those passionate to learn how to read well would find the necessary guidance, silence, and complicity of disciplined companionship.

To those raised to crave the stimulation of the screen, Steiner’s houses of reading probably sound like claustrophobic prisons. For those raised in the tradition of print literacy, they may seem like serene enclaves, havens of learning and contentment, temples to the many and subtle pleasures of the word on the page. In truth, though, what Steiner’s vision most suggests is something sadder and much more mundane: depressing and dwindling gated communities, ramshackle and creaking with neglect, forgotten in the shadow of shining skyscrapers. Such is the end of the tragedy we are now witness to: Literacy, the most empowering achievement of our civilization, is to be replaced by a vague and ill-defined screen savvy. The paper book, the tool that built modernity, is to be phased out in favor of fractured, unfixed information. All in the name of progress.

Christine Rosen is a senior editor of The New Atlantis and a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

What the Grand Vizier needed was a

What the Grand Vizier needed was a  A. The Beginning - As computers began to expand human’s ability to store and analyze data, they did little to help us share data, collaborate, or communicate more effectively.

A. The Beginning - As computers began to expand human’s ability to store and analyze data, they did little to help us share data, collaborate, or communicate more effectively. A. The Beginning - Before the web became the multi-billion page monstrosity that it is today, there was originally disagreement on the best ways to organize all available web sites and information. During these early years, directories and search engines battled for supremacy of web search. Tim Berners Lee, the father of the World Wide Web was also responsible for the first web directory called the WWW Virtual Library. Other popular web directories that popped up during the early years of the Internet included the EINet Galaxy web directory in 1994, and the Yahoo! directory, also in 1994.

A. The Beginning - Before the web became the multi-billion page monstrosity that it is today, there was originally disagreement on the best ways to organize all available web sites and information. During these early years, directories and search engines battled for supremacy of web search. Tim Berners Lee, the father of the World Wide Web was also responsible for the first web directory called the WWW Virtual Library. Other popular web directories that popped up during the early years of the Internet included the EINet Galaxy web directory in 1994, and the Yahoo! directory, also in 1994. A. The Beginning - As web crawling spiders continued to gain intelligence and proficiency at navigating and indexing the Internet, new tools were needed for organizing the data that was being accumulated. Early search engines were able to help users find some of what they were looking for, but were incredibly simplistic. The search algorithms that were used to deliver search results from the data crawled by the spiders simply matched the search terms being searched for, and returned the result to the user in the order that they had originally been crawled. It was clear there was a better way.

A. The Beginning - As web crawling spiders continued to gain intelligence and proficiency at navigating and indexing the Internet, new tools were needed for organizing the data that was being accumulated. Early search engines were able to help users find some of what they were looking for, but were incredibly simplistic. The search algorithms that were used to deliver search results from the data crawled by the spiders simply matched the search terms being searched for, and returned the result to the user in the order that they had originally been crawled. It was clear there was a better way. A. The Beginning - During the mid and late 90’s there was a virtual free-for-all of new search engines coming to market, each with slightly different offerings, but none that stood out significantly more than others in terms of their technology or ability to serve relevant results. It was during this time that spammers and scammers began to realize the profit potentials of manipulating the search engines for their own benefit.

A. The Beginning - During the mid and late 90’s there was a virtual free-for-all of new search engines coming to market, each with slightly different offerings, but none that stood out significantly more than others in terms of their technology or ability to serve relevant results. It was during this time that spammers and scammers began to realize the profit potentials of manipulating the search engines for their own benefit. A. The Beginning - Search engines before Google focused on using the content of the pages they indexed as the best way to determine what the page was about. As discussed, this method was very prone to manipulation because the variables used in ranking could all be easily manipulated by the webmasters themselves. These inherent problems led to the emergence of an entirely new model for search engines, a model that relied on impartial outside sources to help determine what a site was about, and how it should rank in the search results.

A. The Beginning - Search engines before Google focused on using the content of the pages they indexed as the best way to determine what the page was about. As discussed, this method was very prone to manipulation because the variables used in ranking could all be easily manipulated by the webmasters themselves. These inherent problems led to the emergence of an entirely new model for search engines, a model that relied on impartial outside sources to help determine what a site was about, and how it should rank in the search results. C. The Game Changer - In the world of search, one of these tools is changing the way we use search engines all together. By taking an already great resource like Google, Yahoo, or any other search engine and making it more accessible to users, the browser add-on called Chunkit! has enhanced an already excellent resource. ChunkIt! searches within the pages of your engine’s results to find your search terms in context. You can then preview the resulting multicolored “chunks” for relevance without clicking on the actual page. Tools like this, and others, add another layer of usability and accessibility to the plethora of resources already available online.

C. The Game Changer - In the world of search, one of these tools is changing the way we use search engines all together. By taking an already great resource like Google, Yahoo, or any other search engine and making it more accessible to users, the browser add-on called Chunkit! has enhanced an already excellent resource. ChunkIt! searches within the pages of your engine’s results to find your search terms in context. You can then preview the resulting multicolored “chunks” for relevance without clicking on the actual page. Tools like this, and others, add another layer of usability and accessibility to the plethora of resources already available online.